ΕΓΓΡΑΨΟΥ

για να λαμβάνεις τα νέα του Archetype στο email σου!

Thank you!

You have successfully joined our subscriber list.

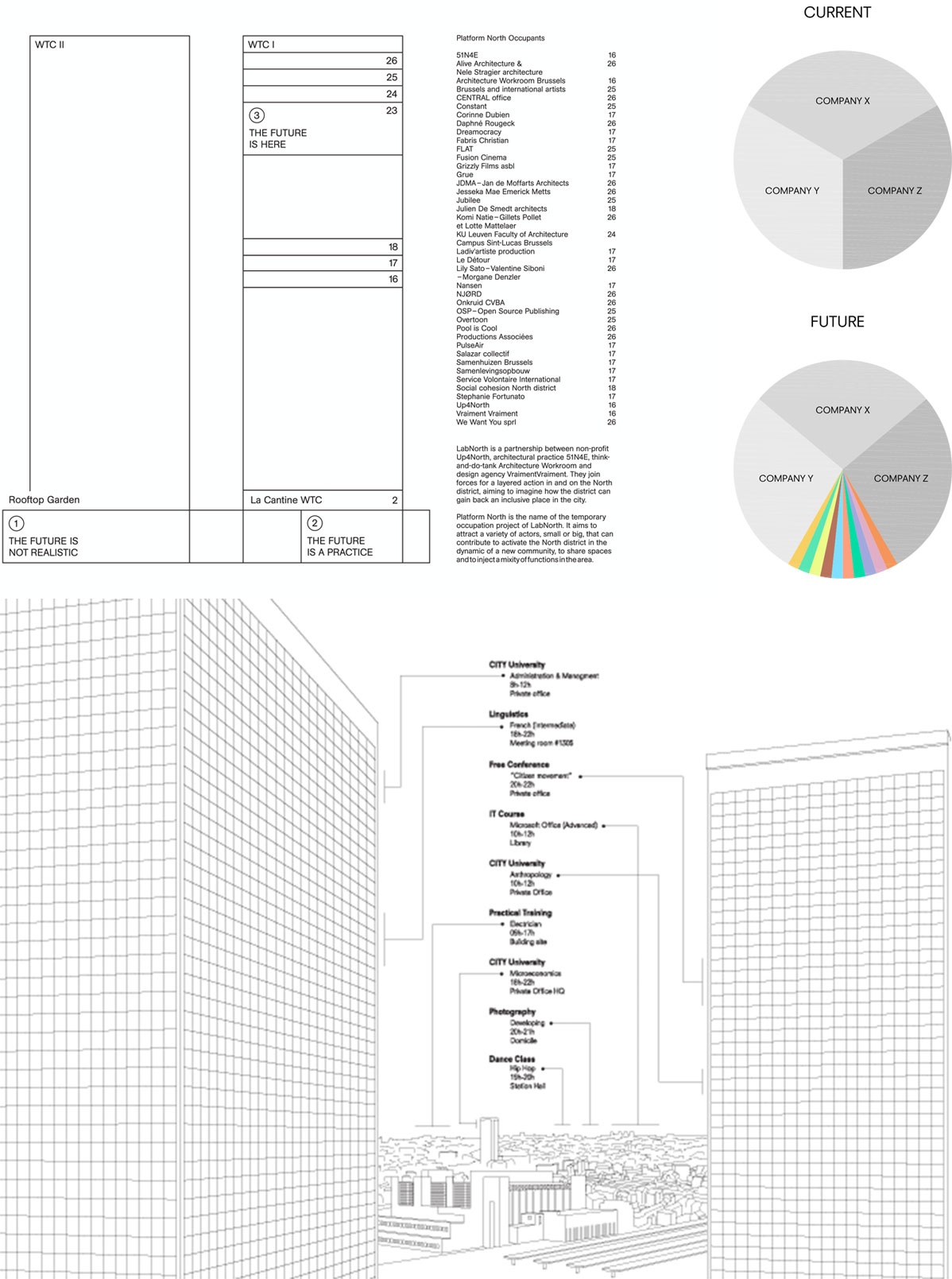

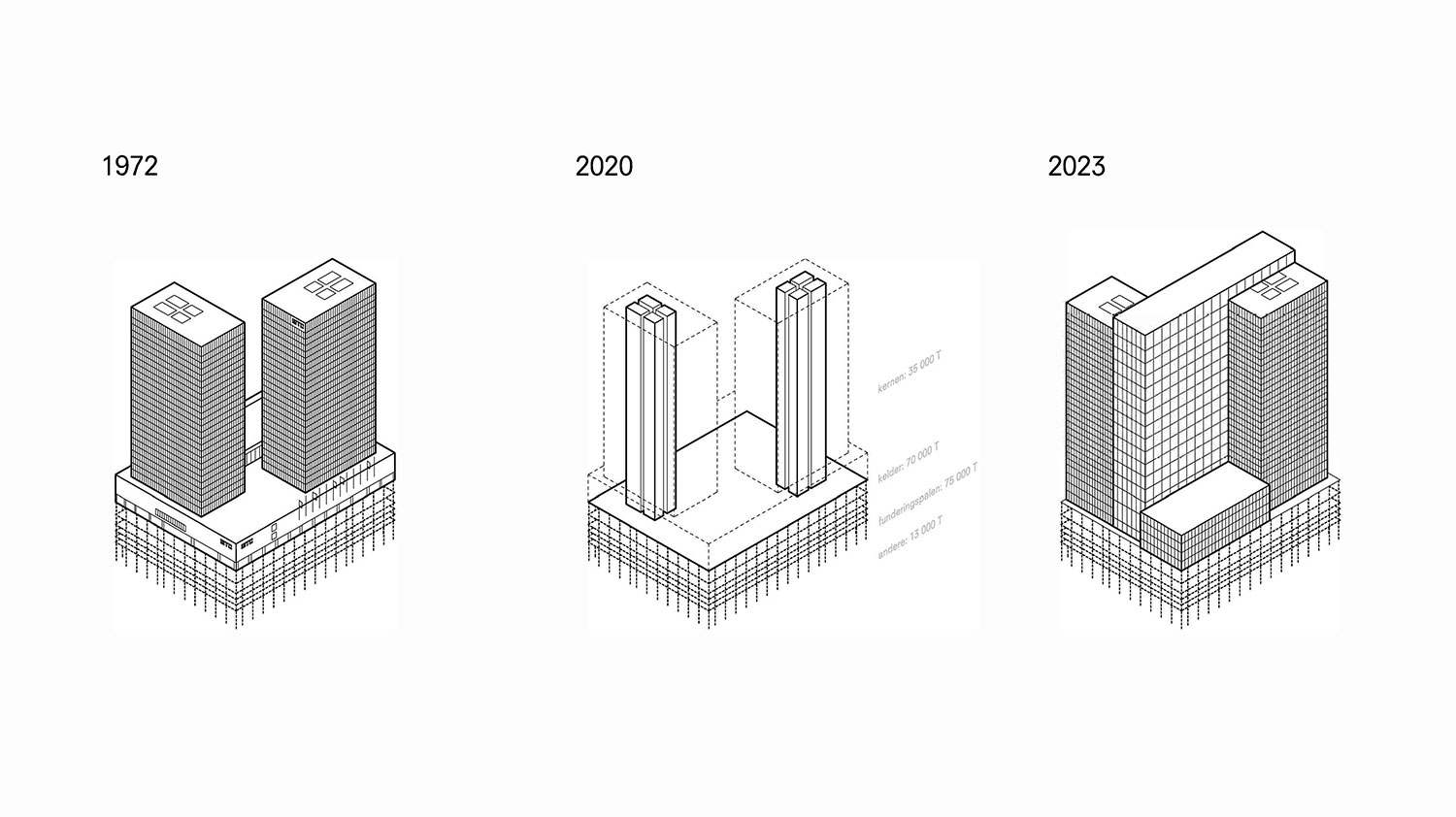

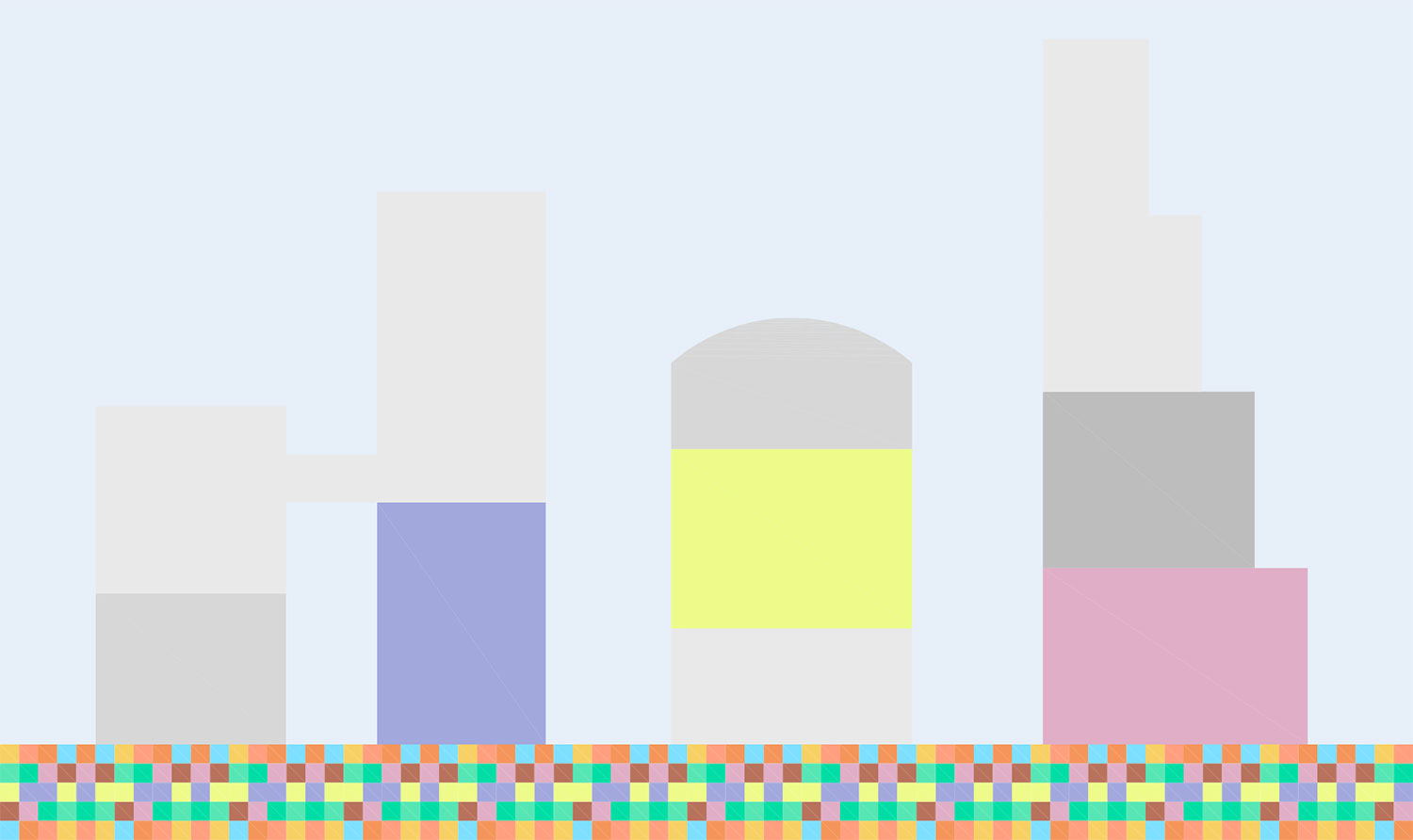

Πριν από λίγους μήνες, οι 51Ν4Ε ανακοίνωσαν το νέο τους πρότζεκτ ZIN-in-Noord. Σε συνεργασία με το γραφείο Jaspers-Eyers και τους L’AUC, το ZIN είναι ένα πρωτοποριακό έργο επανάχρησης των Πύργων 1 και 2 του Brussel’s World trade Center, που στοχεύει να θέσει νέα δεδομένα στον τομέα της κυκλικής επανάχρησης κτηρίων (circular construction). Ωστόσο, για να κατανοήσουμε πιο ολοκληρωμένα το έργο αυτό, καθώς και τη δυναμική ανάπτυξης που έχει πυροδοτήσει, οφείλουμε να μελετήσουμε το περιβάλλον στο οποίο αναπτύχθηκε μία τέτοια πρόταση, και τη διετή δυναμική διαδικασία που το ενέπνευσε. Στη συνέντευξη αυτή, ο Dieter Leyssen μάς μιλά για το ξεκίνημα του Lab North και τα πρώτα πιλοτικά πρότζεκτ που οργανώθηκαν ως in situ πειράματα. Επίσης, συζητήσαμε για τον νέο ρόλο των αρχιτεκτόνων σε μία τέτοια δυναμική διαδικασία, που βασίσθηκε στην παρουσία τους στην περιοχή (the agency of presence), τις δυνατότητες ενός κενού χώρου (the potential of vacancy), καθώς επίσης και τη στροφή σε μία μορφή ανταλλακτικής οικονομίας, όπου για παράδειγμα ιδέες, εξειδίκευση και ενέργεια ανταλλάσσονται έναντι χώρου. Ο Dieter Leyssen μάς παρουσιάζει ένα φιλόδοξο πρότζεκτ που θα αλλάξει τις Βρυξέλλες, στοχαζόμενος τις προκλήσεις αλλά και τις μελλοντικές επιπτώσεις μίας πρακτικής, που επικεντρώνεται σε μικρές, καθημερινές εμπειρίες και χωρικές μετατροπές. Στόχος: ένα εναλλακτικό αστικό μέλλον, ικανό να ενσωματώσει τις χωρικές και κοινωνικές εντάσεις που αντιμετωπίζουν οι σύγχρονες μητροπόλεις.

A new scale inserted in between the WTC tower. In the center: double height spaces connecting the two towers. Credits:51N4E

‘’Do you North?’’ μας ρωτάει το Lab North, μία ομάδα που δραστηριοποιείται στις Βρυξέλλες από το 2016 και ιδρύθηκε από το αρχιτεκτονικό γραφείο 51N4E, το think-and-do-tank Architecture Workroom Brussels, το design agency Vraiment Vraiment και τη μη κερδοσκοπική οργάνωση Up4North. Η ομάδα αυτή συγκροτήθηκε με σκοπό την ανάπτυξη μιας κριτικής ματιάς απέναντι στα σχέδια ανάπλασης του Διεθνούς Κέντρου Εμπορίου των Βρυξελλών (World Trade Center), καθώς επίσης με σκοπό να φανταστούν και να σχεδιάσουν εκ νέου τον Βόρειο τομέα των Βρυξελλών, ως έναν τόπο πολυπολιτισμικό και πυρήνα κοινωνικής συνοχής. Κατά τη δεκαετία του 1960, ο Βόρειος τομέας των Βρυξελλών τέθηκε στο στόχαστρο των οραμάτων πολιτικών ελίτ ως το νέο επιχειρηματικό κέντρο της πόλης –ένα είδος Μανχάταν, με ψηλούς πύργους και φαρδιές λεωφόρους. Σήμερα, η περιοχή όπου επικεντρώθηκε το σχέδιο ‘’Μανχάταν’’ βρίσκεται σε αναβρασμό, λόγω του ολοένα αυξανόμενου ρυθμού εγκατάλειψης και ερημοποίησης των πύργων γραφείων. Το φαινόμενο αυτό οδήγησε στην έναρξη μίας ευρείας συζήτησης, που ξεκίνησε το 2017 και συνεχίζεται μέχρι σήμερα, με θέμα το μέλλον της περιοχής, τον χαρακτήρα και τον ρόλο της για την πόλη τα επόμενα χρόνια.

The WTC towers today.Credits: Filip Dujardin

Nafsika Efklidou: How did the idea come to initiate Lab North and get involved with the North district?

Dieter Leyssen: Two, three years ago, there was a general interest for the office based in Brussels to have a more active role in the city and a personal interest from my side and Freek’s side, because we were working in the city, we were both living in the city. A lot of our projects are in Flanders, in France, in the Netherlands, in Istanbul, quite far from our daily lives and we really missed to have an involvement in our own context. Then, we got the opportunity to teach a workshop in the university of Hasselt on the topic of adaptive re-use, the topic and the site of which we could completely choose ourselves. We were coming back from a meeting on the train passing by the North District and discussing that it would actually be very interesting to work on this modernist heritage, instead of going again to industrial buildings or monuments. Maybe we should apply adaptive re-use to such buildings, instead of more ‘’traditional’’ topics. And then things went rather fast, in the sense that we met people from Up4North, which is an organization working with the big owners of the district and they were playing with the idea to install a meanwhile use, a temporary use to the vacant sites of the North District in the same year. So, for them our idea to run a workshop there came very ideally. In terms of management, we also took a large part in the organization of the workshop to show that it was very interesting (and more feasible) to think about the district, when you are in the district, overlooking it. That became clear also when we were in this World Trade Center office tower, which was almost completely vacant and the students got a lot of energy, in the sense of possibility to change things.

That links of course to the larger context of Brussels, where especially then the office markets were in crisis and there was a lot of vacancy both in the North District and the European District of empty floors that could not get rented. international firms and large public agencies were moving to new buildings leaving the old office towers completely vacant. So, there was both from the real estate side a burning platform of what shall we do with all these square meters, and from the civic side a need for space, especially from the artists’ communities and the architecture offices that are flourishing. Certainly, we were not the first to think about meanwhile use, this has been happening by Toestand, for instance, an organization which has built up expertise in taking over empty buildings and installing a social ecosystem with users, with policy makers. It has been boiling already for some time in Brussels because of these vacant buildings. What happened in the North District was that there was a connection to large companies, which had a lot of floors, and what the modus operandi normally is to rebuild the place and look for a new tenant. So actually design an entire project on the same site and then go to the market or go to roadshows, to look for a large corporation which would rent that new design and then build it. But there was not enough interest for those new designs which all looked a bit the same, but more contemporary. So, the owners were also in doubt what to do next with their site.

NE: Could you give us a bigger insight to the context of the North District, its character and history?

DL: The North District is still an important urban trauma for Brussels, since it was a very lively district next to the North station with bars. It was a workmen’s neighborhood and, in an attempt, to modernize the country in the 1960s, the entire district was tore down, leading to the eviction of 11.000 people and the building of this new modernist utopia that would attract international banks, international corporations and would lift Belgium to the level of London, Amsterdam and other international cities. What was interesting is that at the time almost all parties from the political array were agreeing on it, from socialists to conservatives, they were all sharing the aspiration to be modern. And then there was a broad growth coalition between policymakers and developers, in the same way that in the United States a lot of redevelopment project were done by similar elites. Of course, it didn’t turn out that great. The district was vacated entirely. And until the 1980s only 30% of this plan was built and the rest was erased land. So, in the middle of the city, you had fields of vacant land on a location where people had their daily lives for a very long time. It was really hard. We did some interviews with people who used to live there at the time, and they saw the popular district, they saw the construction and they saw also for 30 years empty land. Until now in the discussion about what is next for this district, you still feel this trauma. For some people it is even impossible to think along with the same elites that are still involved in the future plans, because they did so much wrong in the past. So, in the first phase, WTC 1 and 2 were built and the North station had an extension. Then, with the oil crisis, everything was slowed down. In the 1980s, with the same plan -but much more downsized and much less ambitious- they filled in the other parts: the whole avenue, the lower buildings. In the end all the towers followed the modernist principle of the socle and the towers, although in the beginning there was the idea to have all the public spaces on the terraces. Normally there would have been passages on the first floor like bridges in the air and the parking and infrastructure on the ground floor and all the pedestrian flows would go on top of it.

The WTC towers standing alone on an empty field. Credits: Coll. AAM/CIVA Brussels. The Manhattan plan for the North district of Brussels. Model and collage of the mobility plan. Credits: Coll. AAM/CIVA Brussels

The scope of Lab North and its impact on the future of the North District

NE: So later your team involved in the university masterclass grew into Lab North, who is involved there and what is their contribution?

DL: In the aftermath of the workshop, we started thinking that if we really want to be engaged in the future of the district, we should be present there and combine our practice with this involvement on site. So, we started discussing the possibility of moving in. We were formerly based in Molenbeek, another district in the city where the aim was also to have an active role as an office but that never worked out. We were already for some time looking for another location where we could try again to have a role in the district, and this seemed like a good opportunity. Architecture Workroom Brussels is an organization with whom we work a lot in projects and their role is to bridge the architectural practice with different levels of policy making and make sure that the architectural culture is inspired by what is on the agenda at the policy level, but also the other way around. And at that moment in time they were looking for a way to collaborate with the Architectural Biennial of Rotterdam and the city of Brussels. They needed space and they needed also a context where their involvement would be relevant. The North District was such a context and the puzzle pieces came together. Vraiment Vraiment is an organization, including graphic designers, architects, designers, political scientists, that works in the design of public politics, on how to involve citizens, different knowledge institutions, policy makers, designers in problems such as mobility or such as working models, and then construct a governance system, using design as a tool. They were already working with Up4North before us. In the discussion with those 4 parties, we started to work out the idea of Lab North as a place where, based on our presence there, we could develop different types of involvement in the district.

NE: What is the scope of Lab North?

DL: Back then, one of our main lines of action was temporal use, organizing the call for new users to fill up the tower for one year and a half, addressing also spatially what would be needed in order to host them. Second objective was to attract and work together with educational functions on knowledge production in the district. The goal was to have both Flemish-speaking and French-speaking universities involved and to have a continuous coming and going of workshops. Of course, when KU Leuven and Sint Lucas were interested to have an entire floor for a year, it was amazing. All the teachers, they focused on the North District, so there were in parallel five or six studios looking at the future of the district. It was really interesting. Of course, this was also a bit problematic, meaning what role does the school take producing this knowledge and disseminating it for free. The third track was what we called the Festival, focusing on transforming the district into a destination, attractive to the whole city, by organizing parties and events on the public space. Finally, the fourth track was the new governance model. How can these first discussions between policy makers, owners and civic society can inform and impact the re-development plans for the District?

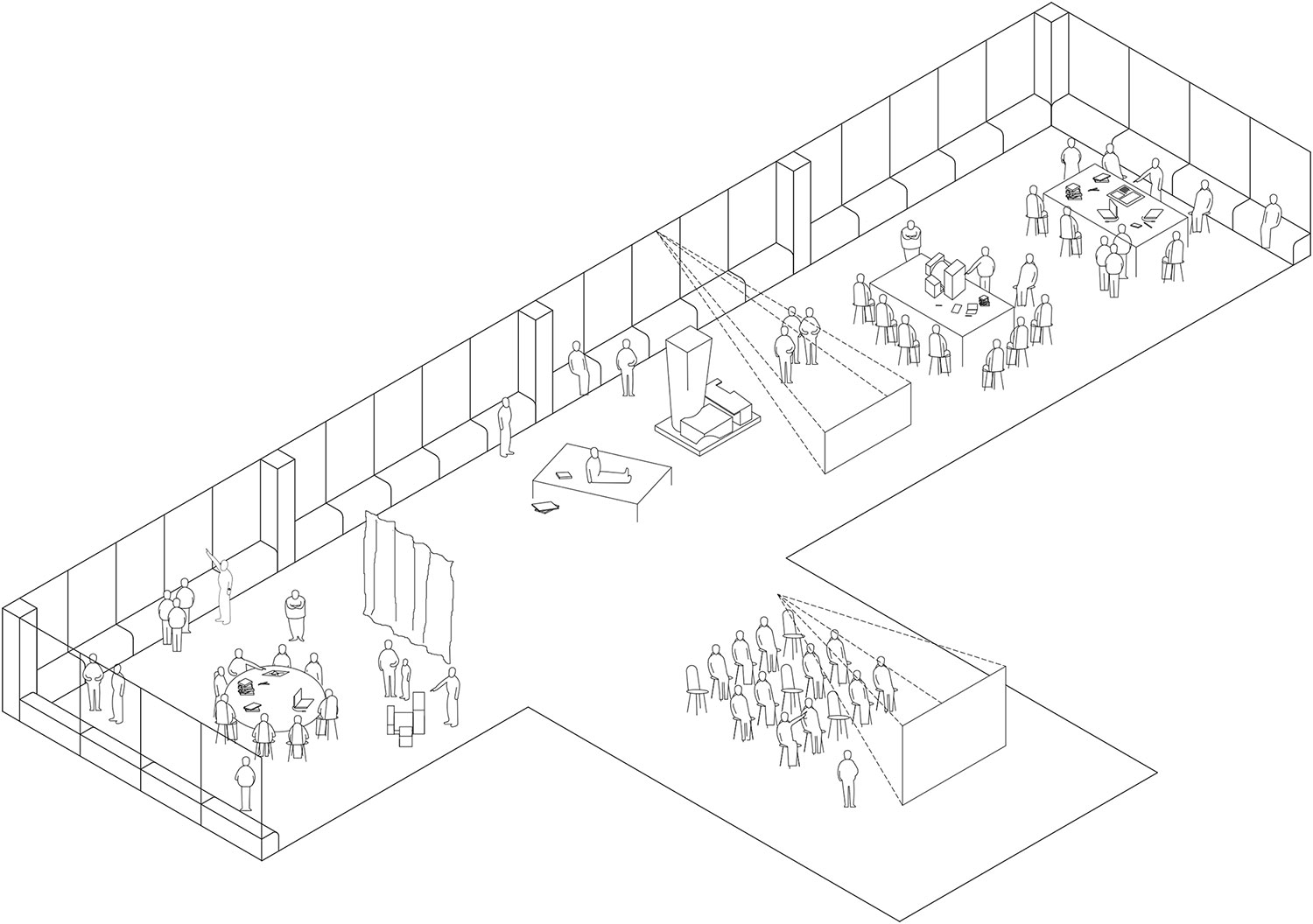

Not only offices but different learning environments in one building. Credits: 51N4E / OK-RM

The growing dynamics of temporary users in WTC I tower. Credits: 51N4E / Vraiment Vraiment / Alexis GIcart

NE: And what was the outcome of this fourth track?

DL: It is still in production. In the beginning, there was very little interest from the public side in the North District because of this trauma. They thought that it was a very sensitive site, because it is also almost completely private land. The streets are public, but they have very little ground there. So, their approach was to let the private owners solve it. However, through our involvement, they started to realize that the district offers a huge potential for the city and if they don’t get involved, it would be a missed chance. In that mindset, the Bouwmeester Kristiaan Borret started to look at the district in multiple ways. Firstly, he involved the Quality Chamber (an instrument of the Vlaams Bouwmeester to consult owners and developers on running projects) with the re-development plans. Another result of our involvement was that the planning agency of the city of Brussels decided to assign someone full-time to work on a diagnostic about how the district should be planned, what type of instruments they should apply and if it should be a masterplan or another more innovative tool. That’s maybe a bridge we can make to the project we are currently working on, because through the involvement of the Bouwmeester with the owners, it was decided to launch a competition for architects to join an already existing team of architects (Jaspers-Eyers) to rethink the renovation of WTC 1 and 2. We were a bit in doubt if we wanted to join this competition, because of our involvement in the meanwhile use. But then we decided to join the competition and use the knowledge that we gathered during the phase of the meanwhile use. So, we applied, there were three other candidates, we built a model of a very simple, but feasible and strong design and they chose us. At that moment, we couldn’t believe what was happening.

NE: So, the renovation was about the existing towers of WTC 1-2 and an addition of an extra tower?

DL: Yes, the competition was also about the addition of extra square meters, by adding a mixed-use building with housing, a hotel, public functions and offices; not another mono-functional office tower. There was a design already as base, but we were completely free to change it. And winning this competition, this was the moment that we started playing many roles in this project: we were users, we were mediators, we were teachers and we were architects.

Adaptive reuse on an unprecedented scale: up to 63% reintegrated. Credits:51N4E

The first year of Lab North and the test phase of the meanwhile use

NE: Regarding the first year and the phase of the meanwhile use, what kind of spatial transformations were done?

DL: There were some very basic transformations done, making the spaces usable and then there were some more transformative interventions. A very important one was when we decided to test a window for the new project in the old building. Now there is no window of the tower that can open, everything is closed and ventilated from inside and we tested one window that could open for 20cm, so you can have a natural breeze of fresh air. This space became one of the hotspots during the Biennial because during summer, you could have a fresh air breeze; people even smoked although it was not allowed. You suddenly felt the very subversive effect of design. It was an aluminum window that you could even see from far, from the canal, a clear spot in a wall of brown glass. And then, there was one very playful, one-day intervention: the fountain turned into a swimming pool and a food track from Pool is Cool, where suddenly the public space became very enjoyable with kids playing in the water. That was during the opening of the Biennial in the WTC.

Simple interventions, like opening a window or rising in height can reveal a hidden quality. Credits: Tim van de Velde / Max Creasy. From a formal fountain surrounded by cars, to a pool with a food truck in the middle of a road intersection. Credits: Paul Steinbruck, Pool is Cool.

NE: How were these small interventions funded?

DL: The little rent that people paid for a working space at the WTC was sufficient to do the infrastructure work in the building. For example, in the 19th floor of the school, they paid the rent so that the workmen of the building could do the extra lighting, electricity, the toilets. Then, we had extra funding for the scenography of the Biennial, sponsored by the Biennial and by the owner also. In the roof terrace, where we made a garden, that was sponsored by the Ministry of Public Life and Mobility. There were small pockets of subsidy to make it work, but of course quite limited and for very specific projects. Finally, us, as an office invested much, making the plans and organizing the testing on site.

On a new role of the architect

NE: If we speculate for a moment your role would have been limited to the phase of the meanwhile use with strategic but minimum spatial interventions. Instead you worked more as mediators between different parties, rather than designers. Do you see that as a positive shift in your practice or do you miss a more active role as designer? I think a similar shift is also taking place in the Greek context, where most architects are occupied with renovation projects and are asked to do the maximum in minimum time and budget. For me there is huge potential in working with existing buildings (not only monuments). For example, in the center of Athens, both the public space and the buildings are suffering from degradation and there is huge room to have impactful interventions, that could even aspire to weave the two realms. Although still a big change in our mindset is needed, both for us as architects/designers and our clients.

DL: I think in the past few years in Belgium we realized that we need to work much more with what is there and the aspiration of building new is gradually getting more limited. It is something you see all over Europe but more particularly in our practice, we are more and more interested in designing/ creating conditions, where transformation and change could happen and creating these conditions often has very little spatial impact. We are often working on transforming relations, on building coalitions, on bringing people together and often the most spatial impact is to create a setting, a kind of scenography, where you can start a discussion. In this light, of course only one of the goals is to have a spatial transformation and I think the creativity of architecture and the capacity of architects to structure a transformation process is as valuable as in designing a space. And that’s the way to increase value in this kind of small renovation projects. Another building that we are working on and relates to this topic is the Submarine Base at Saint-Nazaire, where we did a rehabilitation of two huge garages, where submarines were entering during the war. In this project, the main question concerned the appropriation of monstrous WWII monuments and not so much about architecture. The question of the icon was completely irrelevant. It was about how do we work with the city and how do we make the space appropriable for the citizens. So, we built a new entrance to enable a new relationship to the water and in the interior, we added a very large, pink terrazzo floor. It became a place that is very heavily used by bingos, by parties, by presentations, for dinners etc, only by working with material, with lighting and by creating relations, like a window, multiple doors instead of one entrance door, all kind of possible relations that you can create with architecture.

NE: Back to the WTC project, in your involvement with Lab North, I would like to address the fact that your working in collaboration with the owners of the towers but they are not really your client, at least they have not been during the phase of the meanwhile use. How is it to work without a client, trying to self-initiate an impactful project?

DL: This is sometimes confusing for people to understand why we are doing this, who is it for, who are we creating value for, so that’s a very important question, but not one that is easy to resolve. From the beginning, what we also did in the workshop was to bring together those owners with people from the policy level, the Bouwmeester of Brussels, and link all of them with civic society, with people like Paul Steinbrück from POOL IS COOL, an organization that then also moved in the WTC and later made the pool in the fountain. They were all there in the panel discussion from the very beginning. So, what we tried to initiate is a network governance model that doesn’t necessarily have a client in the center but is closer to a representation of the city (at least that is rather our utopian goal because you can never add everybody). I think this is a big shift and it is happening now in Brussels, but I think also in other cities, where civic society is taken more seriously and large corporations are very much aware that they should take into account the demands of smaller organizations and the city as a whole.

Monopolisation of spaces by big companies is no longer sustainable and healthy for the district. The ambition of a multi-tenant model. Credits: 51N4E

Challenges In the process and the ambition of Lab North

NE: Since you worked so much with public authorities, what kind of hurdles did you encounter during the process?

DL: The situation we created, which is the interdependency of multiple actors is both the strength and the weakness of the project. There is very little accountability, there is no form of framework in which we fit and which we can use to hold people accountable. At the same time, this interdependency keeps everything working, because we all know that we are in it together and if one goes out, everything falls apart. So, we all have a sense of responsibility, but sometimes it can be very confusing and if there is lack of trust, it gets scary because a lot is at risk. We, as a practice of 40 people, we are interdependent on this coalition, because we are moving back to the North district. Another thing that is sometimes frustrating is that through the open call we filled almost half the tower with organizations, the school and a lot of professionals, who are all engaged to build a critical audience for this project and are also engaged in activism: but in the end, for who is this project? And in relation to the trauma, what is the actual goal of it? This is an aspect that is easily criticized, but also very hard to discuss with the whole community we have built. For the context of Athens, I think it is also interesting, where I saw a distinction between those who work together with public authorities and the elites and activist organizations, who do not even engage in dialogue, because they distrust one another, not to mention collaborate. The same tension I feel here in Brussels, because when you work from the inside, together with the developer, together with the political elite, you are easily criticized by outsiders. And while it could be a very productive tension, there must be ways to make this discussion more productive, more democratic and open.

NE: In the end, for you and 51N4E, what is the goal of this project? What is your ambition?

DL: I think the goal for this project is to really test a new way of urban governance, where you work with what is there, you work with the existing fabric of the building, which is very different from the tabula rasa we usually start with and you try to incorporate as many urban actors as possible. Maybe we will have another broad coalition like in the 1960s, hoping that the current coalition can be even bigger and better informed. I think this is the biggest challenge in urban re-developments: how do you incorporate those who don’t want to be incorporated or are just not heard, the minorities, but also those who don’t have time for all this, who have four jobs to have bread on the table. There are some interesting initiatives in Brussels working at the moment on this. Another ambition we have is to test what I discussed earlier as politics of presence, how being present enables a lot of relationships between very different actors. This is something we need to start realizing in architecture that it is not ok to go to China and build a tower without engaging with the local context. That is a true problem in the sustainability of large-scale projects. If you do take it seriously, you need to be there and you need to work on those relationships in parallel with the development of the project.

NE: It seems to me that in such a project, in the end you are also engaging in policy making. Do you believe that by designing processes, you might be undermining urban planning institutions that are in place? Do you think that sometimes bottom-up initiatives might be de-valuing and disregarding towards public institutions, and instead might work in favor of private interests and projects of gentrification?

DL: I think I agree with that. There is a risk regarding the bankruptcy of political authority. Policy makers and city planners are also looking for ways to do things differently, to go away from the modernist way of planning which is a very bureaucratic way of planning. If you could organize a coalition, where they learn from private developers, from architects, from the civic society about how to re-organize public planning, then they could benefit from that. In London, there is a very interesting public practice that engages for short periods good architects and urban designers in public authorities. It is an attempt to attract talent and also make sure that they stay up-to-date with new practices. Brussels is also evolving in a very interesting way, critically questioning their planning instruments. Projects such as this can be an input for this evolution.

NE: And what were happy surprises that you encountered during the process?

DL: Talking about interdependencies, in another interview we called them scratching islands in the tower. For example, we had at one moment, an event organized by the school of Architecture on the 24th floor on the subject of ‘’Agency and the Role of Activism’’, addressing the question for whom are we doing this project, while on the 23rd floor there was a big party organized by the developer presenting the new project. At a certain point, when both parties were over, there was a spill-over; people from the 24th floor checking what was happening on the 23rd. I went to both events and you felt that this is a unique situation: to have these two environments so close to each other, even spill over. And even though the developer was not at the critical discussion of the other event, it was discussed by me and there was a sense of awareness, while in other projects, such events happen in very distinct locations. These were always the nicest moments for me. Maybe that links to the evolution in the Brussels context, because the project is unique in its location and size, but this is the capacity of temporary use as a not-so-clear condition, requiring people from the civic side to invent how to talk and work with private owners and the city. However, meanwhile use shouldn’t be instrumentalized as a tool before re-development or as a phase before Sketch Design. Once you start to formalize it too much, you lose its power.

NE: What is the future of the project?

DL: In the next phase, we will move to WTC 4, where the ground floor, first floor and the roof terrace are available. The purpose of being there is to scale up once more our involvement to address the scale of the entire district. We were very active in WTC 1 and 2 during the Biennial and the phase of the meanwhile use. Now we have gathered a lot of information and we want to be a very active district hub. In the ground floor, there will be a big model of the district, where people can see all ongoing projects that are taking place, such as other temporal uses among others that could be made broadly accessible. Then we aim also to grow the coalition towards those we couldn’t reach yet, or those who are maybe interested to move to the district but have doubts. We are now working with Perspective Brussels to start a one-year Matchmaking program, to map the different agents in and around the district who could have a more empowered role and then we are planning 4 working sessions with them to understand better what their interests and ambitions are and try to link them to the re-development projects in the district. For example, if there is another building that will be renovated or tore down and rebuilt then we can make the match to those actors, that could temporarily inhabit it. The other layer is what we call now the Innovation Platform. In the ground floor there will be this large open space with the model, while on the first floor there will be space for more intense workshops with policy makers and other experts, curated also by Architecture Workroom Brussels to discuss about topics such as the climate, mobility and productivity in the district.

Dieter Leyssen holds a MSc in Architecture (KU Leuven) and is candidate MSc in City Making and Social Sciences (London School of Economics and Political Science). In 2013 he became part of Brussels-based international practice 51N4E. Since 2018 he has taught at the MSc in Architecture, Urban Project programme of the KU Leuven.

Archetype team - 05/03/2026

ΟΛΑ ΤΑ ΤΕΥΧΗ

SUBSCRIBE

ΟΛΑ ΤΑ ΤΕΥΧΗ

SUBSCRIBE

Μπορείς να καταχωρήσεις το έργο σου με έναν από τους τρεις παρακάτω τρόπους: